“Always show your working out!” was the mantra of my maths teacher in senior school. This series of blog posts “On the Nature of Lean Portfolios” is an exploration of Lean Portfolios. It is the thought processes running through my mind, exploring the possibilities so that I understand why things are happening rather than just doing those things blindly. It is not intended to be a fait-accompli presentation of the Solutions within Lean Portfolios but an exploration of the Problems to understand whether the Solutions make sense. There are no guarantees that these discussions are correct, but I am hopeful that the journey of exploration itself will prove educational as things are learnt on the way.

Portfolio Forecasting & Road Mapping

Previous blogs explored the topic of using Weighted Shortest Job First and the conclusions drawn were that WSJF alone is not enough to manage a Portfolio; other activities are necessary to allow a Portfolio to make informed decisions. The Weighted Shortest Job First algorithm also requires supporting activities, particularly the Time Criticality component of WSJF can’t be assessed without an understanding of timelines and for that a Roadmap is required.

The focus of the current set of blogs is Portfolio Level Roadmapping. The previous blog looked into “Why do we need to roadmap?” and covered some of the challenges that Portfolio Level Roadmapping faces.

This post covers some practical facilitation techniques. Presented here in the context of the Portfolio; these techniques aren’t exclusive to the Portfolio and could be used by anyone that needs to create a roadmap.

Practicalities Of Portfolio Roadmapping

Outcome Base Road mapping

Rather than a roadmap specify what needs to happen, a sequence of solutions, the roadmap can contain Outcomes that are desired and the deadlines by which those outcomes are needed. By specifying the Roadmap as outcomes, rather than work items, it gives the teams the flexibility around how they achieve those outcomes and empowers them to come up with solutions.

This is Design Thinking’s separation of Problem and Solution. The Roadmap exists in Problem Space, the outcomes on the roadmap are problems to be solved, which empowers the Trains and Teams. Items on the roadmap should describe “What” needs to be achieved rather than “How” to achieve it. The tension here is that enough of the “How” needs to be known to provide an estimate, but the estimate itself only needs to be accurate enough to reserve about the right amount of space on the roadmap and to provide enough forecasting insight to determine whether corrective action needs to be taken.

Deferring the design of the solution is also an embodiment of SAFe Principle #3 : Assume Variability; Preserve Options and empowering the teams to come up with the solutions embodies SAFe Principles #8 : Unlock the intrinsic motivation of Knowledge Workers and #9 : Decentralise Decision Making.

Collaborative Road mapping

Road mapping is another activity that can benefit from the “all hands” approach that PI Planning utilises. The act of everyone creating the roadmap collaboratively generates alignment amongst the group and gets individuals with differing needs to see and understand other needs that are drawing upon the same fixed set of resources.

- Gather the participants that will assemble the roadmap. The participants required are those stakeholders that place requests on the portfolio (or trains) time. If a capacity guardrail is being used then make sure that representatives from each portion of the capacity allocation are present.

For Portfolio roadmapping the group of people would typically be the Epic Owners and the Lean Portfolio Management decision makers.

For Train roadmapping the group of people would typically be the stakeholders to the Train including the Business Owners and the Train level roles of Product Management, System Architect and Release Train Engineer.

- The process requires a long wide space, a wall of whiteboards or a long boardroom table is ideal. Divide the space up into segments that represent timeboxes within the time horizon over which the roadmap is being developed. For Portfolio road-mapping exercises this will be Program Increments over a year or two.

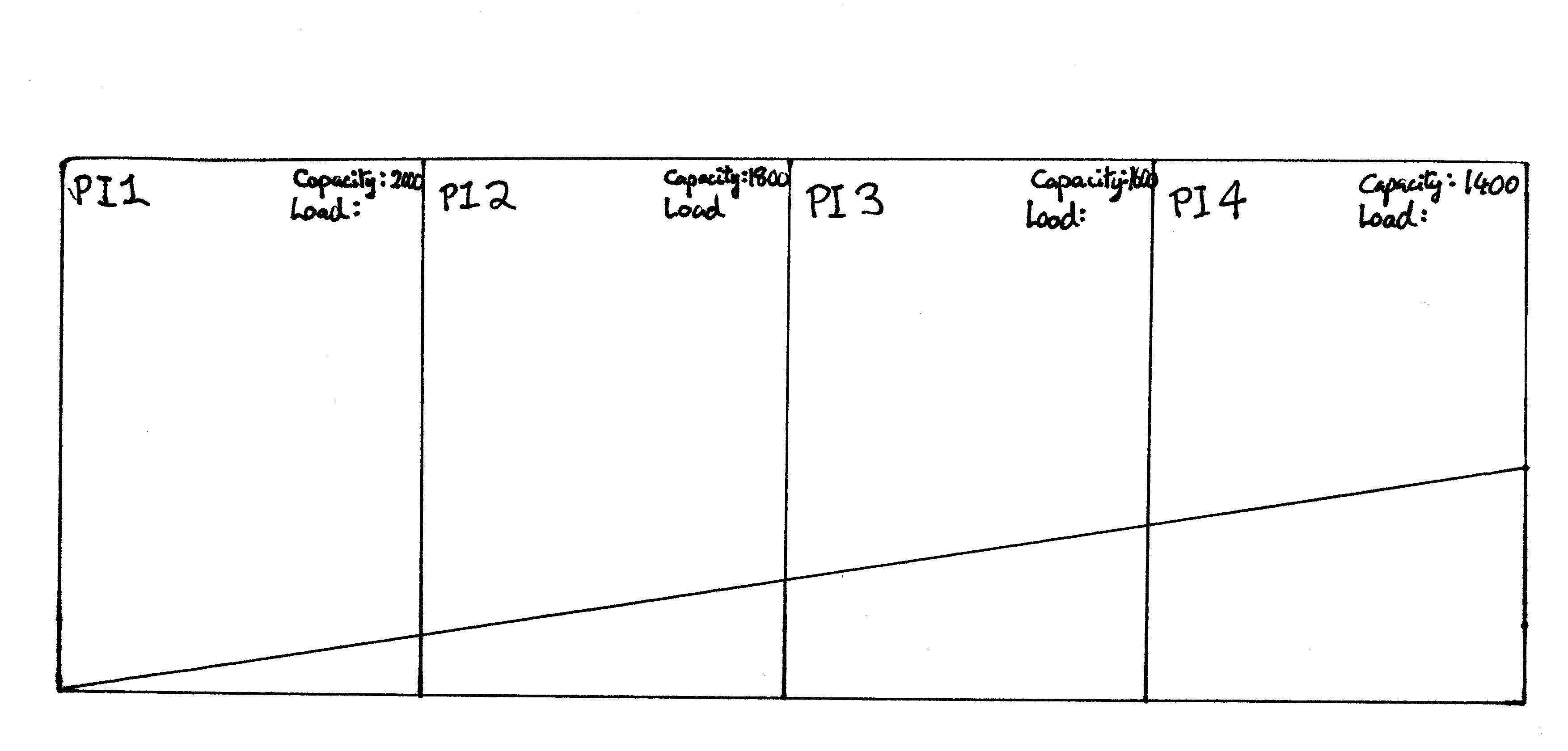

- Using the latest historical data from the Trains for their velocity each PI can be given a capacity; written on a Post-It at the top of the segment for that PI. I like to taper the velocity off over time, successive Program Increments are 80%, 60%, 40% of the current capacity. This represent uncertainty in the capacity going forwards but also the expectation that new work will be found that consumes the reserved capacity; if no work is found then later stages of the roadmap are pulled forwards. It’s trying to pro-actively manage expectations and get participants to understand and embrace the uncertainty and variability that is inherent in problem solving.

- Mark out the capacity allocation available for Business work and Internal work1.

- All of the Work being considered needs a name and an estimate, ideally the estimates have been done in advance by engineering representatives. The owner of the work item receives a Post-It representing that work item.

- The vision is described, usually by the most senior person in the room. Key dates are highlighted and corresponding markers added to the roadmap.

- The participants can now discuss their work items and place them on the roadmap. As items are placed onto the roadmap the loading for a PI can be calculated by summing together all the estimates. The loading should be below the available capacity.

- If the work items are Epics then they will need to be sliced into pieces that fit within the relevant timebox. Try to remain outcomes based for the slices, what are you trying to achieve rather than work to be done. This leans towards the Lean-Startup mentality and helps with WSJF as described in an earlier blog post on WSJF using Experimental Effort

- Is the sequencing right? Is the work necessary to achieve an outcome being done before any associated deadlines? There is likely to be some negotiations to move items around the roadmap to get the sequencing right.

- The representatives of the engineering discipline, Enterprise, Solution or System architects can look at the upcoming work on the roadmap and ask themselves the question “Is there anything that needs to be done earlier to support future deliveries?” They can create Enabler features and add them to the roadmap.

- The process repeats until either the work or available capacity is used up.

- Check for bottlenecks particularly resource or skill constraints. Is there too much work-in-progress?

- Are the guardrails being honoured? The two guardrails directly applicable to Portfolio Road Mapping here are Capacity Allocation and Investment Horizons. Continuous Business Engagement should be handled by the Business participating. The Epic Approvals isn’t applicable at this stage.

If the above sounds a little like the team breakout session of PI Planning but with Epics or Features as the workitem instead of Stories and Program Increments instead of Sprints/Iterations, then you’re on the right track and you probably already know how to facilitate the event.

Visualise and Limit WIP

SAFe Principle #6 – Visualise and limit WIP , reduce batch sizes, and manage queue lengths; roadmaps provide a way for visualizing and managing WIP.

The challenge, particularly at the Portfolio level but can occur within ARTs where the Teams are component aligned, is that the work cannot always be distributed evenly across the Portfolio. It becomes necessary to understand which Development Value Streams / Trains are working on pieces of the Epic. One way to visualise this, to enable management of the problem, is to divide the roadmap up into rows for each Train and plot out which Epics, or pieces of an Epic, each Train could be working on. With the roadmap organised by train it’s a lot easier to see potential WIP infractions.

In the above Example: DVS 3 in PI 1 and DVS 2 in PI 2 are both exceeding their capacity. This wouldn’t have been visible if the roadmap were being constructed for the set of trains rather than collectively visualising the individual train level detail.

If the detail in the roadmap gets too much, if the detail becomes solutions, then such roadmaps could become an imposition on the team and because it’s all been planned out for them they lose their empowerment and the system starts to fall apart. Try to keep the roadmap outcome focused, try to keep it high-level; just enough detail to visualise and resolve the WIP issues. One practical trick for helping ensure that the trains have choice and can manage demand is to utilise the “Pull Mechanic”; rather than pushing work into the teams roadmap the work item, the Epic, is read out, and the train representatives create a ticket in their row if they need to contribute to the work item that has been described. It is a subtle psychological trick but “do you need to contribute to this?” is a lot more empowering than “you’ve got to do this!”

Scenario Planning – Pathfinding

You don’t have to think of these roadmaps as a simple linear sequence; consider scenarios. The roadmap could be a decision tree. Experiments derived from the Lean-Startup mentality form a branching point on the tree and the results once know would send the Portfolio in one direction or the other. Whilst the results from the experiment aren’t known until the experiment has been run, how the organisation should react can often be considered in advance; these form the decision tree.

The decision tree approach allows rationalisation around worst-case scenarios, check that if these were to occur then are the dates, the deadlines, still achievable. Remember that the roadmap isn’t fixed, if the happy path occurs rather than the worst case then work just gets pulled forwards and the roadmap and forecasts can be adjusted to reflect the latest information.

Where is the Truth?

Roadmaps provide intent, an idea of what the higher level would like to happen in the future. That intent informs the lower levels, trains and teams. It can provide them with a vision and an idea of what needs to be created in their backlogs. The Train and Team use these as inputs to their planning. What happens when the plans and information coming back from the teams doesn’t match the information that was on the roadmap?

The basic assumption at work is that the lower level information coming up is always more accurate than the high level information going down because the information is coming up from the people that will have to do the work and they know their owns skills the best. It’s exactly what is meant in SAFe Principle #8 – Unlock the intrinsic motivation of Knowledge Workers when Peter Drucker talks about “the workers must be heard and respected”. That new information needs to be fed into the roadmap and the roadmap recalculated, capacities of trains may change, estimates on work items will change as more knowledge is gained, the estimates may go up, the estimates may go down.

With the truth being fed back into the roadmap it is possible to reassess whether deadlines can be met. If the assessment is that they can’t be met then corrective action needs to be taken; deprioritize or defer work to ensure that those work items contributing to the deadlines receive the focus and get done. If the assessment is that regardless of corrective action a deadline can’t be met then the deadline needs to be renegotiated. The worst thing that can possibly happen is that the higher levels just assume that the lower levels will magically take care of things when the numbers are telling them otherwise; something needs to change at the upper levels.

Who Facilitates?

Facilitating these activities falls to the APMO, Agile Program Management Office2. Discussed briefly in the Lean Portfolio Management article on ScaledAgileFramework.com the APMO are the facilitators, the Scrum Master equivalents, at the Protfolio level. They facilitate the processes that the decision makers in the Portfolio use to run the Portfolio. They can also help gather information and crunch numbers to support the decision makers in the Portfolio in making their decisions.

What Next?

The next article will look into what special considerations need to be accounted for when trying to assemble the roadmap for an Epic which will complete this trio of posts on Roadmapping.

#1 Internal capacity is colloquially referred to as Architectural capacity although that’s a mistake because the type of work, eg. Architectural Enablers and the source of the work Internal (the Train) vs External (the Business) is separate dimensions. It’s the source that determines which capacity allocation it comes from and internally generated work may be more that just architectural work, it could be learning activities or even new functionality that the train wants to implement. Similarly externally sourced work coming from the Business could be requesting architectural improvements as much as new functionality; the work type is irrelevant, if they’ve requested it it’s coming from their budget.

#2 Scaled Agile have been trying to remove the word “Program” from their material because people keep misunderstanding it. They initially used it in the very old-school sense of “a group of people doing a set of work” and in the SAFe world view that work would be a sequence of Features not a sequence of Projects. If you’re reading this in the future then Program might finally have disappeared, in favour of something else. If you’re reading this in the future it might be referred to as Value Management Office (VMO).

More Great Topics for Agile Teams

How many Features do you take to PO Planning? PI Planning Tips

On the Nature of Portfolios; WSJF Estimating Portfolio & WSJF

Program Level WSJF & Feature Slicing Program WSJF & Feature Slicing

All about Managing Dispersed Planning; WSJF Estimating Dispersed Planning Series

States of Epics The EPIC lifecycle